Hacking Prison Architect's Names In The Game

Posted Friday 01 August 2025 at 11:20

Estimated reading time: 19 mins

Prison Architect for a long time had a “Name In The Game” DLC. This was effectively a crowdfunding bonus, a neat way for the developers to raise some extra money to fund the game’s development, whilst allowing those interested to leave a mark in the game that could appear at random in other players’ games. Name In The Game was discontinued in 2019, and, whilst the existing names remain in the game, if you want to add a new name to the game or edit the name/bio you’ve already paid for, you’re out of luck.

Or at least you would be without hacking the game files.

The names in the game are all stored within the game’s asset files, so if you’re willing to dig around, you can add, remove, or otherwise modify as many names as you want. In the past, these were all stored in a human-readable text file called names_in_the_game.txt, and adding a new name by hand was pretty trivial. In around 2018, however, this was changed to names_in_the_game.bin, a binary file with an undocumented format. Modifying this correctly and without breaking anything is much more of a challenge, and one that I’m certainly up for!

A Brief Introduction to Prison Architect Mods

Loosely speaking, Prison Architect’s built-in mod support is essentially an asset replacement system. The contents of your mod directory are injected into the game when loaded with mods enabled. Mods can add new assets of their own, or overwrite the game’s existing assets. names_in_the_game.bin is treated the same as any other game asset, so can be overwritten by mods. This gives us an unobtrusive and impermanent way of changing out the names in the game.

The basic structure of a mod is a directory containing two things:

- a

datadirectory, containing all of the assets we want to inject into the game. - a

manifest.txtfile, which contains the mod metadata.

At first, the only asset we’re looking to replace is names_in_the_game.bin, so this is the only file we need in our data directory. We can extract this from the original game files. In the game’s installation directory is a main.dat file, which is just a standard RAR archive containing its own data directory. Inside here, we can find the original names_in_the_game.bin and extract it to our mod directory. The manifest for this mod is pretty simple too; I just used the following:

Name "Hacking Names In The Game"

Author "Joshua Barrass"

Description "Modify the names in the game."

Version 1.0

IsTranslation false

If we now start up the game and check our mod list, we’ll see this new mod. Now it’s time to figure out how this file works!

Understanding Strings

If we open up names_in_the_game.bin in a hex editor, we are immediately confronted by a lot of strings. Even in the first 256 bytes, we can see lots of obvious strings:

00000000: 7870 0000 486d 0000 3003 0000 0400 0000 xp..Hm..0.......

00000010: 4164 616d 0700 0000 4368 6565 7461 6804 Adam....Cheetah.

00000020: 0000 0044 6965 6c13 0000 0041 6461 6d20 ...Diel....Adam

00000030: 2243 6865 6574 6168 2220 4469 656c 0a00 "Cheetah" Diel..

00000040: 0000 3139 3836 2e30 372e 3237 ef00 0000 ..1986.07.27....

00000050: 4d65 6368 616e 6963 616c 2045 6e67 696e Mechanical Engin

00000060: 6565 7220 616e 6420 6365 7274 6966 6965 eer and certifie

00000070: 6420 456d 6572 6765 6e63 7920 4d65 6469 d Emergency Medi

00000080: 6361 6c20 5465 6368 6e69 6369 616e 2e20 cal Technician.

00000090: 4265 6361 6d65 2061 206d 6572 6365 6e61 Became a mercena

000000a0: 7279 2061 6674 6572 2073 6572 7669 6e67 ry after serving

000000b0: 2069 6e20 7468 6520 552e 532e 204e 6176 in the U.S. Nav

000000c0: 793b 2068 6f6e 6f72 6162 6c65 2064 6973 y; honorable dis

000000d0: 6368 6172 6765 2e20 4172 7265 7374 6564 charge. Arrested

000000e0: 2062 7920 434c 4153 5349 4649 4544 2061 by CLASSIFIED a

000000f0: 7420 5245 4441 4354 4544 2077 6869 6c65 t REDACTED while

We have the forename, surname, nickname, and the formatted combination of the three; the date of birth; the bio; and more as we go deeper into the file. None of these strings are null-terminated, however, so these are not standard C-style strings. If we look closer, we can see a different pattern. Before the four-character string “Adam”, we see the bytes 04 00 00 00; before the seven-character string “Cheetah”, we see the bytes 07 00 00 00. These are little-endian 32-bit values corresponding to the numbers 4 and 7, respectively. These are all, therefore, length-prefixed strings, using 32-bit words for the length.

Now we understand how the strings work, and we’ve also uncovered a little extra information in the process: the word size. Of course, there are no guarantees that every number in this file is going to be a 32-bit integer, but this at least gives a starting point for further exploration of the file.

Exploiting The Word Size

We know now that the first name in the file is Mr. Adam “Cheetah” Diel. The length-prefixed string for his forename starts at offset 0x0000000c, 12 bytes into the file. With our 32-bit (4 byte) word size, that would imply exactly three values precede the first prisoner! Let’s take a closer look…

00000000: 7870 0000 486d 0000 3003 0000 xp..Hm..0...

Upon first inspection, there’s nothing special about this. They don’t appear, for example, to be more length-prefixed strings. So what could they be? The first of these values is 0x00007078 = 28792, the second is 0x00006d48 = 27976, and the third is 0x00000330 = 816. The first thing I notice here is that the last two numbers sum to the first: 27976 + 816 = 28792. Prison Architect allows you to build both male and female prisons, so what if…

There we have it! The first number it seems corresponds to the number of names in the game. If we try changing it to 1 (bytes 01 00 00 00), then the names in the game list updates and only Mr. Adam “Cheetah” Diel appears in the list. Now, there doesn’t seem to be any easy way of determining the gender ratios in-game, and changing the other two values seems to have no obvious effect on the game, even when filtering the names by gender. That said, there are considerably more male prisoners in the game than female, so I’m willing to hazard a guess that this was the original purpose of these second and third values. Whether it’s a redundant feature of the file, or whether I’ve just not delved deep enough to establish their purpose, I don’t know. This first value however, is absolutely crucial for adding our own new names to the game; incrementing this value will allow us to add a new prisoner to the file and have them show up in the game, rather than just replacing existing names.

Optional Strings

Currently, for each prisoner, we have:

- Forename — string

- Nickname — string

- Surname — string

- Full name — string

- Date of birth — string,

"%Y.%m.%d" - Bio — string

Some of the prisoners at the start of the list, those who paid for the “face in the game” DLC, have custom mugshot art. This is, once again, just a length-prefixed string that comes after date of birth. Most, but not all, prisoners also have a skin colour a few bytes after the mugshot path. Again, this is just a length-prefixed string, encoding the skin colour in hexadecimal RGBA as a string literal. For example, for Mr. Adam “Cheetah” Diel, "0x9e6329ff". The inclusion of an alpha channel in this is funny; whilst I haven’t found any prisoners with transparent skin, the game seems perfectly capable of rendering them.

So what about prisoners who don’t have a custom mugshot? Or those who didn’t specify a skin colour? Or those with no nickname? Well, fortunately, the use of length-prefixed strings makes this easy for us. If a string is optional, we just set the length to 0 and move on! The vast majority of prisoners in the file don’t have a custom mugshot, so they do exactly this to avoid specifying one.

Let’s Start Breaking Things

This addresses a lot of the low-hanging fruit of the format now. We understand the header of the file and the string format, which is already quite a lot of the information we need to create our own prisoners. However, after the first five strings encoding the prisoner’s basic info, we have a few numbers we still need to figure out. Their purpose is not obvious from the outset, so how can we figure out what all of this does? We have two main options: 1) compare between different entries to see what looks the same and what looks different, and 2) start changing numbers and find out what breaks!

We understand everything up to and including the path to the mugshot image. What’s left? Here’s how our old friend Mr. Adam “Cheetah” Diel’s entry ends:

00000140: 0000 0064 6174 612f 6d75 6773 686f 7473 ...data/mugshots

00000150: 2f32 3238 3835 392e 706e 6700 0000 0000 /228859.png.....

00000160: 0080 3ffb 7d03 0002 0000 000a 0000 0030 ..?.}..........0

00000170: 7839 6536 3332 3966 66e8 0000 00ff dede x9e6329ff.......

00000180: ff00 0000 00ff ffff ff00 0000 00 .............

So the first number after his mugshot… is zero. Seems uninteresting. What about the next entry, Mr Adrian “Corporate Lackey” AwYoung?

000002ca: 6461 7461 2f6d 7567 7368 6f74 732f 3132 data/mugshots/12

000002da: 3539 3837 2e70 6e67 0000 0000 0000 803f 5987.png.......?

000002ea: 23ec 0100 ffff ffff 0000 0000 d700 0000 #...............

000002fa: ffca c0ff 0000 0000 ffff ffff 0000 0000 ................

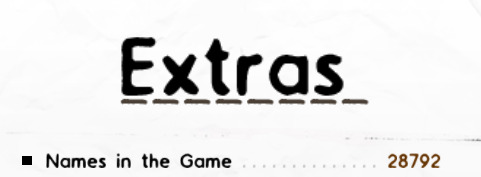

Also a zero. So what do these two have in common? Well, if you compare their mugshots side-by-side, you’’ see that they both have the same body shape: a long, thin, pill shape. These two have custom mugshots, though, so we aren’t able to test this theory on these two. Let’s go back to our friend drunkapple, whose entry ends

0083cf30: 6361 6e21 0000 0000 0200 0000 0000 803f can!...........?

0083cf40: 158e 0600 0800 0000 0a00 0000 3078 6362 ............0xcb

0083cf50: 3934 3663 6666 ffff ffff 0000 0000 0000 946cff..........

0083cf60: 0000 ffff ffff 0000 0000 ..........

We don’t have a mugshot here, so there’s an extra 0 after the bio where the mugshot path would be, but after that is a 2, and we know that drunkapple doesn’t have the pill-shaped body. Let’s try changing this 2 to a 0.

Changing that 2 to a 0 clearly gives them a differently-shaped body, which appears to be the same pill-shaped body as the others. That’s another field cracked!

The next number we see is 0x3f800000 = 1065353216. This number seems way too big to be something as simple as an index for another body part, and it’s a number that seems to be the same across every prisoner I can see on initial inspection. Let’s go to plan 2! Let’s try changing that 3f byte to ff and see what happens.

…ah. Well, that’s an interesting outcome. So we know this value has something to do with the body, but what exactly? Let’s change it back and change the 80 to ff instead.

That’s interesting; the body’s back, but wider than it was. It’s clearly been stretched out, because the edges are also more jagged and blurred. This number clearly controls the scale of the body, then; but what’s the format of it? A scale generally isn’t just an integer, we usually want to represent decimal points, like 0.5, or 1.25. In this case, what if the number is a floating point?

Interpreting a floating point by hand is a little bit tricky, so let’s use Python’s struct package to unpack it. We’ll assume the same 32-bit word size, i.e., a single-precision floating point number. So what do all of the different values we tried correspond to?

>>> import struct

>>> struct.unpack("<f", bytes([0x00,0x00,0x80,0x3f]))

(1.0,)

>>> struct.unpack("<f", bytes([0x00,0x00,0x80,0xff]))

(-inf,)

>>> struct.unpack("<f", bytes([0x00,0x00,0xff,0x3f]))

(1.9921875,)

It seems like all of these values are consistent with the idea that this value is a 32-bit float corresponding to the body scale. The default value used by most prisoners is 0000 803f, which corresponds to 1.0, i.e., the standard default body size. The second value we tried corresponds to negative infinity, so it makes sense that things break when we use that value; a negative scale, and an infinite one at that, is bound to create whacky behaviour. But the third value corresponds to just under 2.0, and matches up with the stretching out of the body. Let’s test this theory by trying to set the scale to 0.25. First, we can use Python again to figure out the float representation of 0.25:

>>> struct.pack("<f", 0.25).hex()

'0000803e'

And that’s that! Instead of stretching the body out, this time it gets compressed inwards, as expected.

(Mostly) Full Picture

The rest of the file can be approached in a pretty similar way — pattern matching against what I can see, or just changing things and seeing what breaks, so I won’t bother going through the process for the whole file. Instead, I leave below the format of the file as far as I’ve figured out (note all strings are length-prefixed strings, as discussed):

Full file

| Data Type | Value |

|---|---|

| int32 | Number of prisoners in the file |

| int32 | Number of male prisoners (unused?) |

| int32 | Number of female prisoners (unused?) |

| Prisoner[] | Array of prisoners |

Prisoner

| Data Type | Value |

|---|---|

| string | Prisoner forename |

| string | Prisoner nickname |

| string | Prisoner surname |

| string | Full name: <forename> "<nickname>" <surname> |

| string | Date of birth: %Y.%m.%d |

| string | Bio |

| string | Path to mugshot photo (can be zero-length) |

| int32 | Body type |

| float32 | Body scale |

| int32 | Prisoner ID number |

| int32 | Hairstyle |

| string | RGBA skin colour in hexadecimal: 0x<RR><GG><BB><AA> (can be zero-length) |

| int32 | Head sprite index (for face in the game prisoners). If -1 (0xFFFFFFFF), then no custom face sprite. |

| Unknown | For most prisoners, 00000000, but differs for face in the game prisoners. |

| int32 | Gender. 0 for male, 1 for female. |

| Unknown | For seemingly all prisoners, FFFFFFFF00000000. |

There are still a few fields here that haven’t been figured out in full. The first unknown field must be connected to the face in the game, as it is preceded by the sprite index (which can be found in the objects.spritebank file within main.dat — they’re each labelled under the BEGIN Sprites header with their index, e.g. BEGIN "[i 237]") and only seems to take a non-zero value for prisoners with custom face sprites. This is something to figure out for the future. The second unknown field seems to be there for every prisoner, and may just be a closing header. It would be interesting to write a parser for this file and find out whether any prisoner exists with a different value here — again, something for the future.

Working Example of a Custom Prisoner

To close out, let’s put all of this together to make our own custom prisoner. To make this easier, we can use the following Python code to pack all the data into the file:

from typing import Tuple, Optional

import struct

import datetime

def lps(s):

return struct.pack("<i", len(s)) + s.encode()

def build_prisoner(

forename:str,

nickname:Optional[str],

surname:str,

dob:datetime.date,

bio:str,

mugshot:Optional[str],

body:int,

body_scale:Optional[float],

id_number:int,

hairstyle:int,

skin_color:Optional[Tuple[int,int,int,int]],

female:bool=False):

if nickname is None:

nickname = ""

if mugshot is None:

mugshot = ""

if body_scale is None:

body_scale = 1.0

if skin_color is None:

skin_color = ""

else:

skin_color = "0x{0:02x}{1:02x}{2:02x}{3:02x}".format(*skin_color)

if female is None:

gender = 1

else:

gender = 0

data = b""

data += lps(forename)

data += lps(nickname)

data += lps(surname)

if len(nickname) > 0:

data += lps(f'{forename} "{nickname}" {surname}')

else:

data += lps(f'{forename} {surname}')

data += lps(dob.strftime("%Y.%m.%d"))

data += lps(bio)

data += lps(mugshot)

data += struct.pack("<ifii", body, body_scale, id_number, hairstyle)

data += lps(skin_color)

data += bytes([0xff,0xff,0xff,0xff,0,0,0,0])

data += struct.pack("<i", gender)

data += bytes([0xff,0xff,0xff,0xff,0,0,0,0])

return data

def append_prisoner(path:str, prisoner:bytes, female=False):

with open(path, "rb+") as f:

f.seek(0)

count_total, count_m, count_f = struct.unpack("<iii", f.read(4*3))

f.seek(0)

if female:

count_f += 1

else:

count_m += 1

count_total += 1

f.write(struct.pack("<iii", count_total, count_m, count_f))

f.read() # skip to EOF

f.write(prisoner)

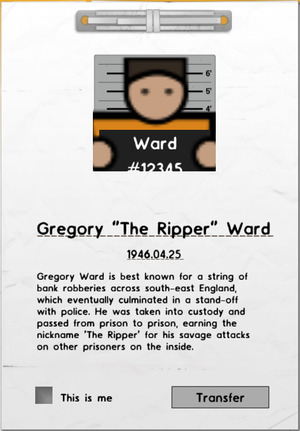

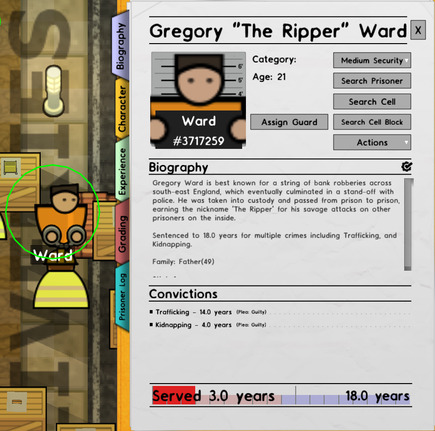

I used Behind the Name to generate a random prisoner name — I’m going to call him Gregory “The Ripper” Ward, born 25 April 1946 — and we’ll just cook up a random bio about him being a violent bank robber: “Gregory Ward is best known for a string of bank robberies across south-east England, which eventually culminated in a stand-off with police. He was taken into custody and passed from prison to prison, earning the nickname ‘The Ripper’ for his savage attacks on other prisoners on the inside.” Let’s feed this into the code:

append_prisoner("path/to/names_in_the_game.bin",

build_prisoner("Gregory", "The Ripper", "Ward", datetime.date(1946,4,25), "Gregory Ward is best known...", None, 1, 1.1, 12345, 1, (0xc6, 0x9f, 0x82, 0xff), False),

False,

)

…and just like that…

…everything works. We can add custom mugshots, too, though these are a little buggy — in the pause menu, the rendered mugshot is still displayed over the top of the custom mugshot, but it works just fine once the custom prisoner is transferred into a prison.

Conclusion

So there you have it! By diving into the names_in_the_game.bin file, we can finally modify and add custom prisoners to Prison Architect, long after the cessation of the official Name In The Game DLC. We have almost as much control as the original DLC offered — perhaps more, with the custom mugshots, which weren’t previously available to Name In The Game purchasers. This opens the game back up to personalisation, whether you missed the opportunity to pay for a name in the game originally, or just want to further customise your existing prisoner. Happy hacking!